On December 3, 1984, more than 8,000 people died in Bhopal, India when a pesticide manufacturing plant owned and operated by Union Carbide Corporation (now Dow Chemical) exploded in the middle of the night. It was one of the worst industrial disasters in history. In the 27 years since, at least 20,000 more have died as a result of this one event and the area surrounding the plant remains a toxic waste site.

People know about Bhopal like they know about Chernobyl. What many don’t know is that the night after the explosion, the company’s CEO hopped on a private jet and fled the country and Dow Chemical has yet to be held accountable.Nearly three decades have passed and the people of Bhopal have yet to see justice and not for lack of trying. There remains a vital international campaign calling on Dow to do the right thing. But Dow is a tough target with thick skin–they don’t care.

Why then, should organizers continue targeting Dow as a bad corporate actor if public shame does not work? Because there is simply no other mechanism of justice available. Big players like Dow, Bayer, Syngenta, DuPont, and Monsanto effectively operate above the law.

We have seen time and again that there is no national government willing to take on the “Big 6” pesticide manufacturers, who together dominate the agricultural input sector (i.e., pesticides and the seeds genetically engineered to go with them). Here in the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is getting cold feet about really pursuing a rigorous re-evaluation of Syngenta’s flagship herbicide atrazine, a ubiquitous drinking water contaminant that also happens to be an endocrine disruptor associated with birth defects, cancers, and more. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Department of Justice (DOJ) have mysteriously backed away from what looked like a promising investigation into the monopoly control enjoyed by the likes of Monsanto and DuPont over the agricultural input market. The list goes on.

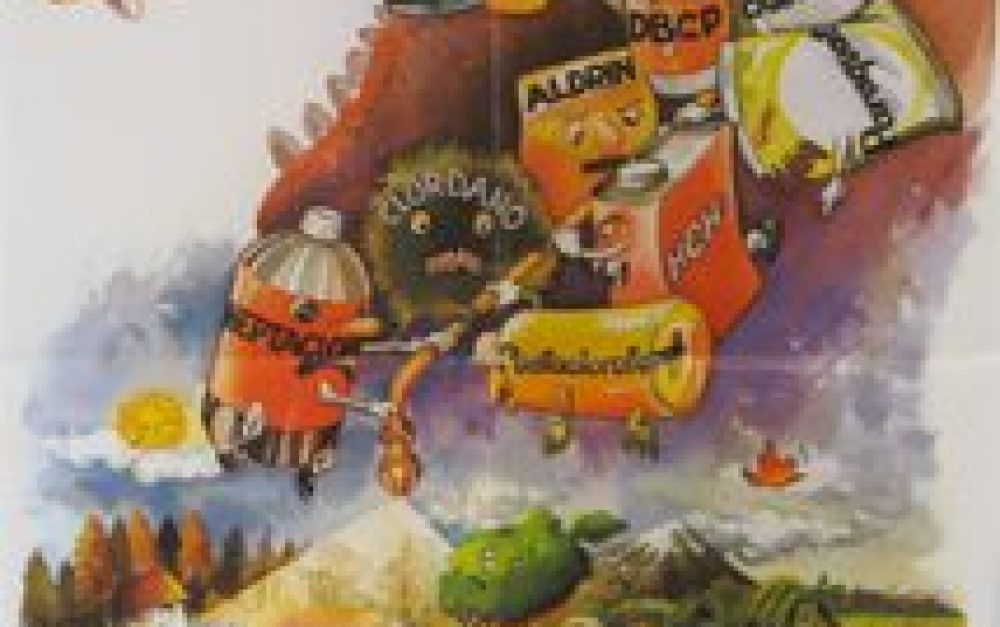

The Original “Dirty Dozen” Campaign

In 1982, when the Pesticide Action Network (PAN) was founded, we faced a similar conundrum. No government agencies were willing to do anything about global pesticide trade and transport. Then it was dubbed the “Circle of Poison,” a phrase that captured the problem of pesticides illegal in the industrialized North being dumped or sold to countries in the South with lax regulations then making their way back up North as residues on food. Long-lasting, bioaccumulative pesticides like DDT were also making their way around the world on wind and water currents and by accumulating up the food chain to contaminate mother’s milk in arctic regions where these pesticides had never really been used.

Sometimes you just have to name the problem & go after it.

There were, and are, dozens of these kinds of globe-trotting pesticides–called persistent organic pollutants, or POPs–but PAN chose to go after 12 of the most highly hazardous ones in order to bring some focus and public attention to a nexus of problems otherwise too complicated to tackle. In 1985 the global network launched the original “Dirty Dozen Campaign” (not to be confused with the Environmental Working Groups’s wallet card). We worked with citizens around the world to track the use and effects of the target chemicals and to press for a ban of 12 pesticides nobody had heard of and few could pronounce. We did so before there any were global governance mechanisms to make this ban happen.

The road was long and arduous and it took the work of many hands. Sixteen years later, we had not one but two international treaties regulating pesticide trade and transport: the Rotterdam Convention on Prior Informed Consent (the “PIC treaty”) and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (the “POPs treaty”). Not coincidentally, more than half of the POPs treaty’s first 12 target chemicals were pesticides on PANs “Dirty Dozen” list. “Circle of Poison” issues have largely been addressed and POPs are declining worldwide.

My point? Sometimes you have to just name the problem and go after it. To wit: the 99 percent.

Toxic Trespassers on Trial

Twenty-seven years to the day after Bhopal, on the International Day of No Pesticides, PAN convened a trial to bring into focus the problem of pesticides today. We no longer have the “Circle of Poison” problem so much as a complete lack of corporate accountability. There is no system of justice or governance adequate to the task of taking on what has quietly become one of the most powerful industries on the planet.

Known as the “Big 6,” the indicted corporations include Monsanto, Dow, BASF, Bayer, Syngenta, and DuPont. Collectively, these interests control 75 percent of the global pesticide market and 49 percent of the global seed market, earning the pesticide/agricultural biotechnology industry the distinction of being among the most consolidated sectors in the world.

There is no system of justice or governance adequate to the task of taking on what has quietly become one of the most powerful industries on the planet.

From December 3-6, 2011, the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal will convene to hear cases brought by farmers, farmworkers, mothers, young people, scientists, and consumers from around the world. The Big 6 stand accused of violating human rights by promoting reliance on the sale and use of pesticides known to undermine internationally recognized rights to health, livelihood, and life.

The PPT is an international opinion tribunal, established as a successor to the Russell Tribunals on Vietnam (1966-1967) and on Latin American dictatorships (1974-1976), to make visible and juridically qualify situations of massive human rights abuses when those violations find no other recognition or redress. While drawing its authority from the people, the PPT proceeds from relevant international human rights laws, precedents, and documents such as the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights. Following the rigors of a conventional court format, violations are documented and presented to a jury who then deliberates and passes judgment.

To what end? We don’t yet know.

In 1996, after the 1992 PPT on Industrial Hazards and Human Rights in Bhopal, the “Charter on Industrial Hazards and Human Rights” was adopted. In 1983, the Tribunal sent investigators into Nicaragua pursuing accusations of U.S. aggression and undue intervention there. One year later, the case was taken up by the International Court of Justice. Chains of causality in global events are often indirect and only assume a kind of order in retrospect.

What we do know is this: Six corporations stand accused of systematic violations of human rights to health, livelihood, and life. And while less recognized in the U.S. than elsewhere in the world, international citizens’ tribunals have a long history of mobilizing public opinion. Governments often, but do not always, follow.

This post was originally posted at Civil Eats