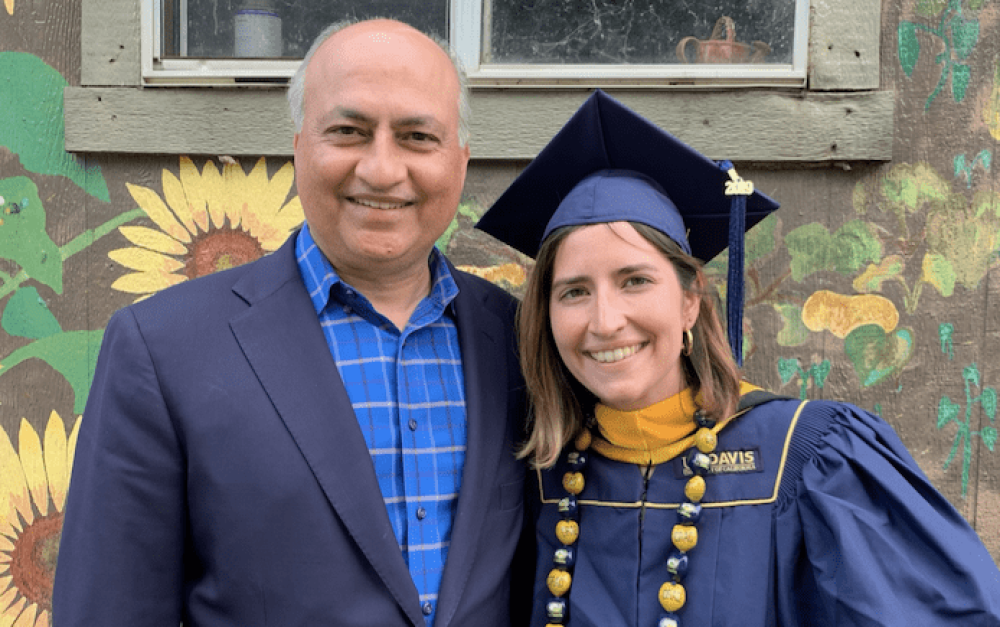

Organizing Co-Director Asha Sharma recently sat down and chatted with her dad — Dr. Jivesh Sharma — about pesticides and cancer risk.

Organizing Co-Director Asha Sharma recently sat down and chatted with her dad — Dr. Jivesh Sharma — about pesticides and cancer risk.

Understandably, not many people have fond memories of hospitals. But I’ve always felt comfortable in them – growing up, my dad was a busy oncologist (cancer doctor) running his own private practice. Visiting his office at the hospital was one of the few ways I got to spend extended time with him. I remember entertaining myself by chasing the robot that delivered medicine to offices around the hospital, and happily scarfing down jello at the cafeteria.

Later, for a couple of summers in college, I worked part-time at the front desk at his office to earn some extra income. Seeing my dad’s dedication to serving his patients, many of whom were fighting life-threatening cancers, no doubt helped shape my own interest in public health and environmental justice. I watched him and his staff screen for exposure risks each time a new patient came into the office, and started learning about how occupational exposure to carcinogens, like asbestos or pesticides, was linked to certain types of cancer.

Since joining the PAN team, I’ve been surprised to see how slow U.S. agricultural policy has been to recognize the cancer risks from pesticide use, while in the medical field, they are widely acknowledged and screened for. So I interviewed my dad — Dr. Jivesh Sharma — to share more about his medical perspective on the connection between pesticide exposure and cancer.

Hi Dad! Can you tell us a little bit about your background, and how you specifically got interested in oncology?

I’m a medical oncologist in Dallas, Texas with a cancer drug development background and a degree in business and technology. As a medical oncologist, I take care of cancer patients. I also practice hematology [the treatment of blood disorders.] I’ve been practicing since 1993 — for 29 years. I wanted to go into medicine because I have a sister with spina bifida [a spinal cord birth defect] and saw that first hand. I also couldn’t believe there was a job where you would get paid to learn about your own body.

I had actually already gotten into a cardiology fellowship, and oncology was a last minute decision. I had a life-changing experience during one of the last months of my residency where I was called into the hospital at 3am because one of my patients was dying. He was a veteran with lung cancer and I sat with him and his wife through the night since we had to manually control morphine drips in those days. He died peacefully that night and I felt that I helped ease his suffering. Afterwards, I had a profound sense that this is what I should be doing with my life.

I know from working at your practice that the initial questionnaire that new patients fill out includes questions that ask about their profession and whether the patient has had occupational exposure to pesticides. Can you explain these questions in further detail and why they are important to ask?

I practice in Texas where some of my patients come from rural areas, and agriculture is a big industry in Texas. There are certain cancers that are more prevalent, or at least have correlations with those occupations. It helps determine the risk allocation to certain potential cancers. I want to screen people for things they are at higher risk for.

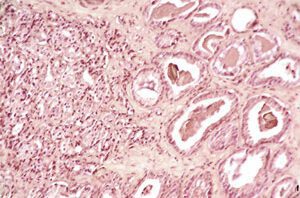

It’s very hard, based on current knowledge, to be specific and say a patient’s cancer is caused solely by a pesticide per se, although there’s been clear correlations between certain herbicides, insecticides and cancer risk, including specific types of cancer. As an oncologist, I do have an understanding of the cancer risks of an agricultural worker. For instance, they can get melanoma [skin cancer] from sun exposure. Lymphomas and multiple myeloma are two cancers that are associated with pesticide exposure. Prostate cancer risk is also higher. Even biologically, the type of prostate cancers that they [agricultural workers] get tend to be more aggressive than the general population. Therefore, I may be seeing an agricultural worker for a blood disorder problem, but I would still need to screen them for prostate cancer as well. Their occupational history affects their treatment, but also screening and long-term care.

Are there any stories of agricultural workers who you treated for cancer that stand out to you?

I remember when a fellow physician asked me to see his mother who had a rare cancer called a neuroendocrine tumor. Then, a year later, his father was diagnosed with the same cancer. It’s uncommon to have rare cancers like that in one family. So I brought them both into the office to talk about familial risk.

It turned out that they were originally from Southern Illinois where they had a farm. All three family members grew up on this farm, and they had memories of working out in the fields where crop dusting planes would come and they would get dusted too. They were all non-smokers and non-drinkers, and the crop dusting exposure was the only risk factor that I could find. The couple later switched to a different business that they owned and didn’t have any subsequent occupational exposures. So to me, that [the crop dusting exposure] was the common factor.

Unfortunately, the mother and father both died, and I ended up screening the physician every year for that specific cancer from then on. He did not develop that cancer but had a couple of spots on his liver that we were monitoring.

How many agricultural workers do you see/what proportion of patients do they make up?

I don’t categorize people as agricultural workers. I typically categorize them as rural versus urban. If they’re in a rural area, they are also around farm equipment, so they are exposed to organic solvents and pollution from machines from farming, which are other cancer risk factors. You also don’t have to necessarily work on the farm for there to be a risk. Everybody is around carcinogens like the crop dusters. Whatever chemicals are being used, they’re not going to be geographically postage stamped. They could get in the water or food supply. It’s an ecosystem.

There is a unique subset of people who are actually in the business of applying pesticides. There are people whose occupation is to provide that service and those people really have to watch carefully, including their spouses. There are good data that show there’s an increase in cancer if you have one of those jobs.

In terms of numbers, 5,500 out of 12,000 total patients [46%] were from rural areas. This includes both of my Dallas, Texas and Tyler, Texas practices.

What public policies do you think should be implemented to reduce health risks for agricultural workers and rural communities who are often on the frontlines of pesticide exposure?

I think education is important and making sure everybody understands there is a risk and what the risks are. You also want to make sure that everyone has access to appropriate equipment to protect them. And you want to reduce the risk of events. You don’t want to crop dust people — you want to let everybody in the area know so they can clear out or wear protective gear.

[Asha here. As an aside, there’s also all the work we’re doing at PAN to transform agriculture so that less of this kind of spraying is happening in the first place!]

Anything else you want to share?

The other thing that I’m dealing with right now is there are more and more patients who are in litigation, especially around RoundUp and lymphoma, and a lot of times I’m asked to testify. If they have had exposure and have a malignancy that is associated with it, I often provide records and an opinion that it probably played a role. Same with asbestos and other exposures.

Most studies we currently have are based on associations. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) has some prospective studies that are following populations of patients with very clearly defined exposures that are really going to help elucidate some of the questions. They are following a cohort of farmers and agricultural workers and looking at their cancer incidents. That’s where they found out about elevated prostate cancer risk. That’s NCI data. There are also other medical correlations with pesticides like neuropathies [damage or dysfunction of nerves].

Also, I’m proud of my daughter, and the work to protect communities from pesticides is very important.