A new report by scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) reminds us that we have a lot to learn about the risks of exposure to multiple pesticides at a time. Hmmmm. “Exposure to multiple pesticides at a time” — isn’t that what we face in the real world? Yes, it is. Read on.

A new report by scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) reminds us that we have a lot to learn about the risks of exposure to multiple pesticides at a time. Hmmmm. “Exposure to multiple pesticides at a time” — isn’t that what we face in the real world? Yes, it is. Read on.

The researchers, who work with UCLA’s Sustainable Technology & Policy Program, looked specifically at exposures to three fumigant pesticides: Telone (or 1,3-dichloropropene), chloropicrin, and metam sodium. Here’s what they found:

- Some California residents are exposed to all three pesticides, either all at once or over a period of time;

- These pesticides can interact in ways that increase risks to human health; and

- California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR) is not assessing the risk of cumulative exposure — which it is, in fact, required to do.

Drifting and dangerous

Fumigant pesticides are highly toxic chemicals that are used to manage pests in the soil. In California, because we have such a diversity of what are called “specialty crops,” we use a lot more fumigants than the rest of the country. Many specialty crops are highly lucrative — some examples are strawberries, lettuce, stone fruits and grape vines — and fumigants allow the planting of the same crop in the same field year after year.

Applied as a gas or liquid, fumigants are used at very high volumes and are vaporized (or volatilize) readily. These two factors contribute to the strong propensity of these pesticides to drift off-target.

Drift into nearby fields, homes, schools and communities is the main route of people’s exposure to fumigants. Every year in California, many farmworkers and residents fall ill from acute exposures to fumigants, as indicated by the state’s Pesticide Illness Surveillance Program. Unlike many pesticides, residues remaining on our food are not an issue with fumigants. These pesticides are so volatile; they’re not likely to stay on food by the time it gets to market.

Not all mixtures are created equal

The researchers point to a number of ways the three fumigants might be interacting, including cumulative effects, additive effects and interactive effects. What does it all mean?

We experience cumulative exposures in the real world — exposure to a milieu of chemicals in our environment, day after day. These cumulative exposures can lead to mounting effects, which can be either additive or interactive. Here’s where it gets interesting — or scary, depending on how you look at it.

Additive effects come into play when two or more chemicals combine to elicit an effect greater than exposure to one chemical alone. “Interactive” effects happen when two or more chemicals interact to increase or reduce a toxic effect. Our best understanding of interactive effects is based on pharmaceuticals, and the potential for some drugs to antagonize and/or synergize with each other.

Oh yes, and then there’s cancer risk

Yes, there is evidence that all three of these fumigants are carcinogenic. Evidence of other effects has also been reported, including developmental toxicity, reproductive toxicity, and neurotoxicity. Yet another way fumigants might impact us is by using up a detoxifying enzyme, glutathione, which we all have in our bodies. When the enzyme gets depleted, we have to make more — and meanwhile the fumigants remain in our body longer, and may cause additional harm.

Share on Facebook | Pin on Pinterest| Tweet on Twitter

Share on Facebook | Pin on Pinterest| Tweet on Twitter

And finally, these fumigants have physical properties that indicate they could attack DNA directly or inhibit the activity of enzymes that control important processes such as DNA repair and maintenance of DNA’s stability, which could also increase risk of carcinogenicity. Here at PAN, we call chemicals that can cause toxic effects like these “bad actors.”

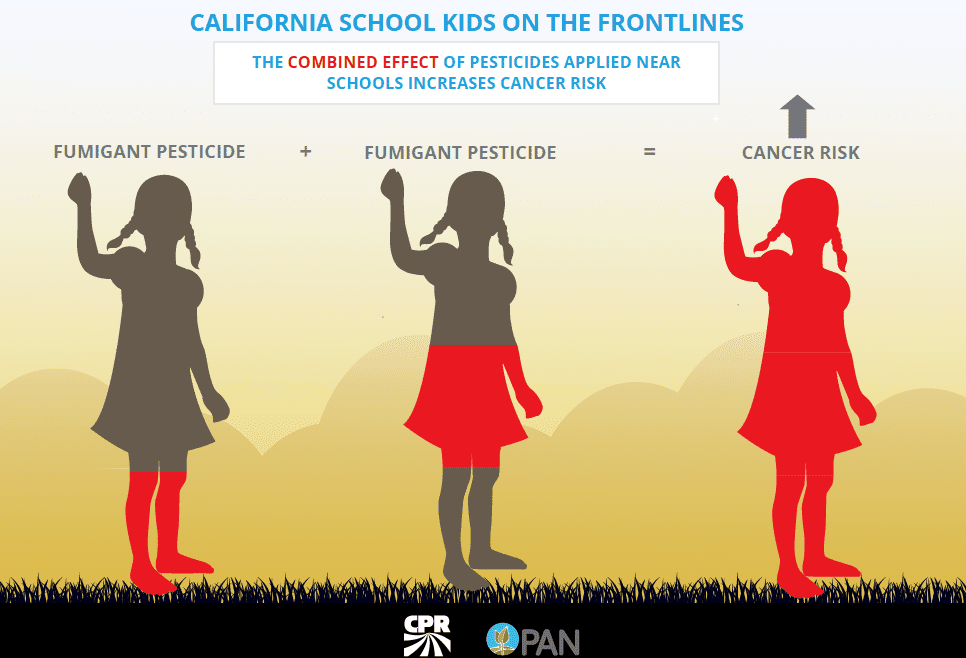

We know fumigant drift is happening at levels that increase risk of cancer. Last fall, we conducted a Drift Catcher project with a community partner in Watsonville, California to monitor for chloropicrin. Even though the levels we found in the air were relatively low, they were still sufficient to increase cancer risk for children and families in nearby homes.

Watsonville is one of the biggest strawberry growing regions in the country, and fumigants are used in many fields every year. During application season, exposure to multiple fumigants — like those highlighted in UCLA’s study — is highly likely.

Protecting human health in the face of uncertainty

You’ll note that I’ve used the words “might,” “possible,” and “potential” a lot here. This is because there is still much that we don’t know, and the new report identifies several data gaps. Knowing this, how do we reduce uncertainty? And what can and should DPR do now to reduce health risks in California communities?

We can reduce uncertainty by collecting more and better data, and using it. Approaches for identifying interactive effects and, more broadly, cumulative risks have been developed by U.S. EPA, California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment and the European Food Safety Authority. It’s quite a challenge to assess cumulative exposures, but DPR can and should use these guidelines to give it a try.

Meanwhile, DPR officials need to consider this new evidence of interactive effects — and then take steps to protect public health. We’ve long known from air monitoring data that fumigants drift in the air. With this new report, we know a bit more about the potential of these chemicals to interact with each other, posing more of a health hazard than was previously thought.

As DPR takes a closer look, they will likely find good reason to put more protective buffer zones in place around schools and other sensitive sites — and maybe even good reason not to use some of these pesticides. This would be very good news for Californians’ health. It should also trigger measures to protect farmer livelihoods, including financial support for alternative approaches that don’t rely on such hazardous pesticides.