PAN stands in solidarity with families that have been impacted by microcephaly and other serious health impacts of the Zika virus.

PAN stands in solidarity with families that have been impacted by microcephaly and other serious health impacts of the Zika virus. Unfortunately, the primary response to the outbreaks to date has been widespread spraying with pesticides to control mosquito populations. Decades of vector management around the world show that this approach is not only often ineffective, it can also compound the risks to human health.

Zika is a mosquito-borne disease, spread by the daytime biting Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, and outbreaks are occurring throughout Latin and Central America — as well as parts of North America. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 2,250 cases had been documented in the U.S. as of August 18, with the states of Florida, New York and California among the most affected. In addition, more than 7,850 cases have been reported in the U.S territory of Puerto Rico.

Urgent action to control the spread of this dangerous virus is clearly needed. Individuals can reduce their risk of exposure with the commonsense steps outlined below, and PAN International urges officials at all levels of government to pursue the safest, most effective approaches to controlling mosquito populations.

Integrated Vector Management works

Experiences from around the world in dealing with mosquito-borne diseases like malaria, dengue and chikunguya have shown the hazards of relying on pesticide spraying as the primary tool to combat vector-borne (e.g. mosquito) diseases.

Mosquitoes rapidly develop resistance to pesticides, leaving the chemicals wholely ineffective. Successive generations of pesticides — from extremely hazardous ones like DDT to the present day use of pyrethroids — have demonstrated this trend. The World Health Organization underscored the problem in their 2012 guidance on policy-making for Integrated Vector Management (IVM):

Resistance to insecticides is an increasing problem in vector control because of the reliance on chemical control and expanding operations . . . Furthermore, the chemical insecticides used can have adverse effects on health and the environment.”

Many of the pesticides used in an attempt to control mosquitoes can be harmful to human health, in both the short and long term. Naled, for example, one of the organophosphate (OP) insecticides being used in response to the Zika outbreaks, is linked to a range of short term impacts including convulsions, dizziness, vomiting and unconsciousness. Long term impacts of Naled exposure can be serious — particularly for children — as it is a hormone disruptor and a reproductive and developmental toxicant.

Many studies have also linked prenatal exposure to OP pesticides to neurological harms, including increased risk of autism and reduced IQ levels.

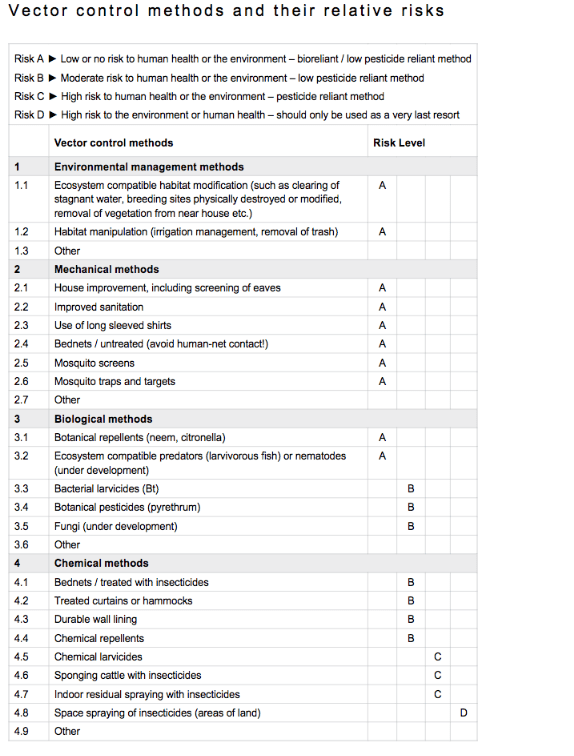

In case after case, vector control relying on a community-based, least toxic version of IVM (see table below) has proven to be much more effective in controlling mosquito populations and, therefore, the diseases they transmit. As PAN Senior Scientist Dr. Marcia Ishii-Eiteman notes:

Investing in least-toxic IVM is a win-win for communities. It’s the best way to both control mosquitoes and avoid reliance on health-harming pesticides.”

Commonsense steps for prevention

Individuals and communities can take effective steps to reduce mosquito populations in and around homes, and to reduce the possibility of getting bitten by mosquitoes. The Centers for Disease Control, the Hesperian Foundation and the Natural Resources Defense Council all provide tips for families and communities to prevent infection with the virus. A few key steps include:

- Preventing mosquito breeding sites by regularly removing sources of stagnant water from bird baths, swimming pools, planters, etc.;

- Preventing mosquito bites by wearing long sleeved clothing and applying repellents with safe biological and botanical ingredients including neem, lemon and eucalyptus;

- Preventing mosquitoes from entering homes by repairing window screens and ensuring there are no unscreened openings through which mosquitoes can enter; and

- Managing water bodies, like backyard or park ponds, that are potential larval habitats for mosquitoes through habitat modification, biological control (e.g., larva killing fish) or larviciding (preferably with biological larvicides).

With the concerted efforts of individuals, communities and vector control agencies, Zika and other vector borne diseases can be controlled safely and effectively — without harming human health or the environment.

See the table below to assess the relative risks of various mosquito control methods. For more in-depth information on IVM, please refer to PAN International’s decision-making framework for malaria control.