I’ve been an earthworm fan for decades. At my Oakland, California home I dump vegetable scraps into a big plastic bin with worms. Once or twice a year I collect incredibly rich worm compost, teaming with roly-poly bugs (isopods), worms — and billions of critters I can’t see. My garden plants love it, and it’s free.

In agricultural soils, worms (different kinds, but worms nevertheless) can contribute significantly to soil respiration with a direct and sharp increase in the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) released, as the number and length of worm canals increases. It turns out this soil respiration is critical to plant health.

Plants combine H2O, CO2 and energy from the sun to create the sugar glucose in the process of photosynthesis. We know where water comes from, but did you know that most of the CO2 that plants need comes from the soil? To mark the International Year of Soils, I’ll be exploring fascinating facts like these in a series of blogs on soil ecology and health, and highlighting the critical importance of earthworms and other soil-dwellers.

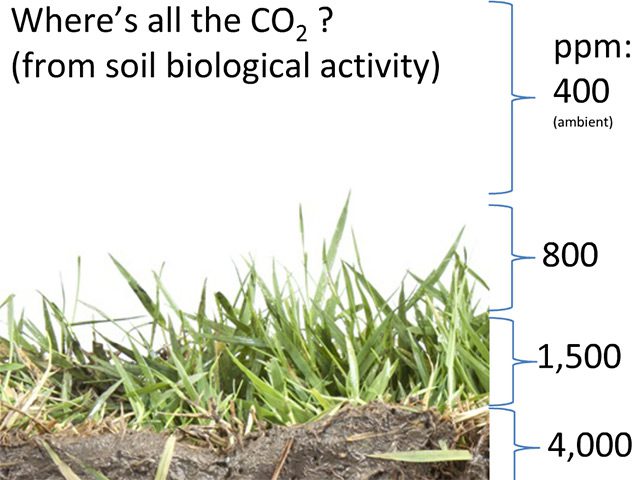

But back to soil respiration. The soil biological community can deliver much more CO2 than what’s available in the air. A teaspoon of healthy soil contains millions of different kinds of organisms, ranging from bacteria and fungi to nematodes and insects. That’s a LOT of respiration — up to ten times what you’ll find in the surrounding air.

Source: W. Brinton; Woods End Laboratories/ USDA NRCS Webinar; April 2015

Also in that teaspoon are the millions of bacteria and fungi responsible for converting essential nitrogen (N) — 79% of the air we breathe — from an unusable gas into forms plants can use. Without N, plants and animals alike would have no proteins — which are essential for just about every process or function of living cells.

What about those worms?

Decades of research has documented a direct, positive impact of earthworms on crop yields. This is no doubt a function, at least in part, of increased respiration.

Not surprisingly, these gentle creatures are quite vulnerable to the scourge of synthetic pesticide use in conventional agriculture. Many commonly used organophosphate, carbamate and pyrethroid pesticides can be lethal to worms — some at levels well below recommended rates of application.

Talk to farmers who have made the shift away from conventional practices to more agroecological practices and you’ll hear stories like how a shift to cover-cropping between crop seasons has greatly improved the level of soil organic matter, reduced runoff and erosion — and increased crop yields. Or maybe how even a one-time application of compost on a pasture can increase plant growth by 25% to 50% by providing food to the soil organisms. Another farmer might explain how she checks her fields periodically for earthworms, knowing that the more she finds, the healthier her soil.

It’s all about soil health

Farming practices, along with the initial nature and condition of the soil, dictate whether soils are healthy and able to provide plants what they need to thrive. In addition to a healthy crop of earthworms, here’s a small sample of what plants are looking for:

- Water when they need it — and not too much;

- Air for both the soil critters and plants to breath, and healthy soil to provide all that CO2;

- Good microorganisms in the right balance, to provide essential nutrients and to protect plants from bad microorganisms like fungi that cause plant diseases; and

- Fungal “roots” — also known as fungal hyphae — that vastly increase the functional root area, scavenging nutrients throught the soil profile and binding soil into clumps that maintain vital porosity for movement of air and water.

Soil ecology is complex and fascinating science. I look forward to digging deep into the workings of the soil microbiome over the coming months; beyond earthworms and respiration to plant health, crop yields and more.