The year is 1977, and the place is Mendocino County, California. A time traveler would be astonished at how much this community has changed. Once a sleepy coastal community, it is now part of the Silicon Valley sprawl. But current residents of small towns would recognize a familiar sight: a spray plane applying herbicides to a nearby field of row crops.

Tragically—but not uncommonly—the pesticides applied on this day end up drifting over three miles from the target crop, exposing several school busloads of kids to phenoxy herbicides. This horrific event galvanizes the community, and two years later, Mendocino County passes an ordinance to restrict this class of herbicides from being sprayed by plane.

Unfortunately, the State of California immediately overturns—or preempts— the local ruling, marking the beginning of a battle that is eventually heard in the California Supreme Court. This is only the beginning—and the resulting debate will affect community and environmental safety for the next fifty years.

Preemption — when one level of government trumps the laws passed by another — has become a focal point for community organizing across social movements, from minimum wage laws to sanctuary cities. When it comes to pesticide policy, preemption is a key hurdle to pesticide regulation progress in communities across the country.

How did we lose local control?

California wasn’t the only state blocking local authority over pesticides in the nineties. In 1991 a Wisconsin case on the same issue went all the way to the US Supreme Court. Advocates were overjoyed when the Court ruled in favor of the people: it was determined that local communities did indeed have the right to put rules in place that were stricter than federal regulations, if they chose to do so.

Unfortunately, the ruling left the door open for state governments to preempt this authority, and pesticide industry lobbyists — wanting to maintain as much influence as possible on policy decisions — sprang into action.

By 1991, a “Coalition for Sensible Pesticide Policy” had been formed by industry lobbyists determined to block communities from adopting stronger pesticide rules. This coalition laid out an aggressive campaign to pass as many preemption laws as they could as quickly as they were able. Soon, pesticide preemption bills were appearing in statehouses across the country.

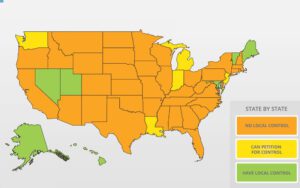

These laws — many using the exact language developed by industry — specifically limit the ability of city or county governments to ban or restrict pesticides in any way, including the “use, sale, notification, marketing, distribution” and more. Before long, 43 states had preemption laws in place.

Such preemption laws do not exist in Canada. Over the past 20 years, more than 170 Canadian cities and towns have outlawed use of pesticides for “cosmetic” purposes such as lawn care. Canadian community activists report that more than 22 million Canadians (65% of the population) are now protected from exposure due to cosmetic pesticide use.

Currently, there are seven states in the US that still retain the option for local control. Local communities have put in place over 150 policies over the years regarding pesticides—policies that are custom-fit to that community’s circumstances and needs.

Another community’s story of loss

Mantrap Township is a small community in the Central Sands region of Minnesota — a place where corporate agriculture has a strong foothold. R. D. Offutt (RDO), the world’s largest potato producer, works the majority of the farmland in this region. RDO doesn’t go light on pesticides — potato crops are sprayed by overhead planes every five to seven days during the growing season.

In 1993, Mantrap Township’s 450 residents passed local legislation regarding aerial spraying. The ordinance they passed would have required applicators to get a spray permit sixty days before use, and disclose information on the risks, benefits, and alternatives to the pesticides being used. Sounds reasonable, right?

Not according to RDO and the state Agricultural Aircraft Association, who both fought the ordinance aggressively. And state courts had to agree — because Minnesota had passed a preemption law just a few years before. State law dictated that Mantrap citizens had no right to make local laws and could exercise no control on pesticide use in their own community.

Communities fight back against pesticide preemption

These policies, passed in the nineties, continue to haunt community members today. Over the last three decades, countless community members in pesticide-preempted states have set out to solve a pesticide-related problem in their community. These individuals have made alliances and compromises, volunteered time and energy on behalf of their communities, and worked with others to develop municipal policies to address pesticide use issues—only to have their democratic rights thwarted by state preemption laws.

Yet each time communities run into pesticide preemption, the demand for overturning these laws grows—including mayors, city council members, and other local officials. During the 2018 Farm Bill cycle, over 60 local officials across the country co-signed a letter in support of local control over pesticides. Five years later, as Congress discusses a new Farm Bill, the cry is loud–and it’s building from the grassroots. From Hawaii to Colorado to Minnesota, communities are taking steps to reclaim their right to local control.

These are the seeds of a potentially successful movement for pesticide progress. And now we have evidence of the backlash from the pesticide lobby. Last year, a bill was introduced in Congress that would eliminate local control across the board, overturning over 150 local policies passed in the 7 states that still retain local control. This bill, authored by Rodney Davis, has been taken hold of by partisan politicians, who (for some reason) are claiming that state and federal restriction of local control should be a top priority.

At PAN, we know that those who are closest to a problem are best equipped to advise on the solutions. Preemption forces us into a cookie-cutter approach to policy that keeps us from responding to issues that impact the local environment, local health, and local economies. As the fight heats up, we’ll be ready—because in our minds, the question isn’t if we’ll restore local control to communities. It’s when.

Photo | Flicker Kevin Krejci