Winter in Iowa, before the snow covers the expanse of corn and soybean fields, highlights how barren it has become. The crops have been removed and, too often, the fields have been turned. Left over the winter, the soil is exposed to the elements and is ripe for erosion. Piles of woody plants, trees and bushes, can often be found at the edges of fields where big equipment has been used to remove what little plant diversity remains. Tree lines, pastures and fields with cover crops stand out as exceptions rather than the norm.

All of this makes it hard not to succumb to the feeling that efforts to change how we farm and grow food will fail. It seems as if things have always been this way and there is no model to promote small-scale, diversified farming. But, that is not true. The trend of larger farms with single-crop fields (monocrops) and large animal confinements is actually fairly new, and we don’t have to look far to find successful alternatives to our current chemical-intensive food and farming system.

Diversified farm operation success in 1878

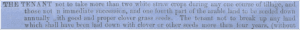

I came across an old agreement to rent a farm in Wales beginning in the year 1878. Like most legal documents, much of the content was not an exciting read. But, I took notice of the sections that outlined how the land should be tended or, using the terminology of that time and place, husbanded.

Part of 1878 farm rental agreement

The owner of this farm was very careful to instruct the new tenant on proper land management. This document illustrates a long-standing approach to maintain diversity and protect the health of the soil that reflects generations, and probably centuries, of successful care and stewardship.

The agreement references the use of longer crop rotations, including perennial plantings, such as a grass and clover mix. The meadows, pastures, waterways and woodlots were given a place in the system and the new tenant was forbidden from turning over certain lands for annual crops — recognizing that not all land is suitable for tillage. Cover crops, intended to put roots in the soil to prevent erosion and improve soil health, were included in the crop rotation. And, of course, animals, with the fertility they provide, were afforded a place in the operation.

At least some of the ideas, if not all, that are a part of agroecology were in place at this farm, and there is evidence that those ideas had a history of success.

War’s residue introduces intensive pesticide use

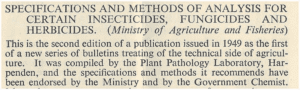

In contrast, I found a booklet from the early 1950s that advertised available publications by the British government. The list included an entry for the second edition of “the first of a new series… of the technical side of agriculture.” The title of the publication makes it clear that the subject matter is the use of pesticides.

Pesticide publication, early 1950s

This second document reflects the rapid development of chemical production for the war effort, except now these chemicals were being commercialized and adapted for use as pesticides with a wide range of applications. DDT and 2,4-D use rapidly spread along with claims that humans could now “win the war” against insects, diseases, and other pests. And, typically, the use of these products were promoted well before the potential consequences were considered and studied.

The rapid rise of 2,4-D

Once the demand for products to support the war effort waned, businesses in the chemical industries were seeking ways to remain relevant and profitable. It should not be a surprise that the commercial hype that came with the creation of DDT and 2,4-D resulted in the rapid expansion of their use, despite insufficient demonstration of their safety for “non-target” organisms, including humans.

I found an interesting series of articles by Dr. Delena Norris-Tull under the title “Management of Invasive Species in the Western USA.” In this chapter, the author effectively reports the story of 2,4-D’s introduction as a tool for the control of weeds and invasive species.

Experts on the ground were immediately concerned about the product’s persistence in the soil and the possibility that it would negatively affect soil bacteria. Early results showed that 2,4-D’s persistence (the period of time it remained in the soil) varied depending on the soil type. Further, the product’s interaction with a range of plants varied significantly. As far as the impact on animals and humans was concerned, there didn’t appear to be any effort or capacity to work on that problem at the time.

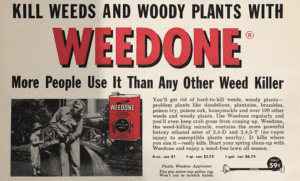

2,4-D advertisement in Better Homes and Gardens, May 1954

Regardless, minutes from the 1946 Western Weed Conference recorded concerns that farmers and ranchers were moving rapidly to put 2,4-D into use without adequate research for the potential damage the chemical could cause. The proceedings from that conference noted that:

“Several sensational articles and advertisements about 2,4-D had appeared in print, and the barometer of public interest was rising rapidly… It was immediately evident that [their] meager facilities and personnel for weed research would not be able to gain information rapidly enough to protect the public interest except through organized effort.”

The Precautionary Principle and pesticides

One of the themes that surrounds the movement behind the reliance on pesticides is the push by corporate interests to promote and secure the right to sell products that could be dangerous without sufficient research and testing. This seems counterintuitive given that the intent of these products is to suppress life.

Instead, it seems logical to adopt the Precautionary Principle when it comes to pesticides. With this approach, the benefit of the doubt belongs to human health and environmental protection instead of to the chemical being evaluated and its commercial interests. This would encourage more safety research prior to product sales and it would result in the removal of products as soon as a risk of harm is shown.

For example, PAN has been working for decades to encourage a ban of chlorpyrifos, a dangerous organophosphate insecticide that has been shown to harm the brain development of children with even low dose levels. If the Precautionary Principle were in place, it would be harder to allow the continued use of products with this active ingredient than it is to ban its use. However, since the EPA does not use this principle, we have had to wage an extended battle and must continue to fight to remove this dangerous pesticide from use in the US.

Agroecology providing better solutions

Corporate interests promote a narrative that food production, and the agriculture industry as a whole, cannot succeed unless there are liberal applications of their pesticide products. What they don’t want people to hear is that there are alternatives and they are embodied within the principles of agroecology — principles that can be used successfully by farmers, but can’t be patented or sold as novel products.

Instead of larger fields and farms with a single crop, agroecology embraces diversity and complexity. Agroecology promotes practices that consider a broader balance sheet that pushes beyond crop yield and farm profit to include soil and community health. And, agroecology embraces the Precautionary Principle by encouraging practices that seek to protect human health and the environment, while still providing opportunities to harvest enough to feed our communities and have successful farms.

The good news is that examples of the successful use of agroecology are not that hard to find in history and there are a growing number of people in today’s world that are motivated to act to implement its practices. Winter will only be with us for a time. Spring is just around the corner.