If there were no other way to control pests, we’d be having a different conversation. But given the fact that there are many proven ways to control pests without the use of harmful chemicals, the choice is quite clear.

It’s time to build a food system that doesn’t rely on the use of dangerous pesticides — with strong policies in place to protect our health and wellbeing and support farmers who find safer ways to control pests.

An old, broken system

A little over 100 years ago, Congress enacted our first national pesticide law. The 1910 Insecticide Act put labeling guidelines in place to protect farmers from “hucksters” selling ineffective, misbranded or adulterated pesticide products.

To this day, we control pesticides through a system of registration and labeling. The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), passed by Congress in 1947, is our primary national pesticide law.

Overlooking real-world risks

FIFRA has been updated several times in the last 65 years, most significantly in 1972 and again when the Food Quality Protection Act was put in place in 1996.

EPA is charged with periodically reviewing the health and environmental impacts of the more than 17,000 pesticide products currently on the market — plus evaluating the risks posed by new products.

Unfortunately, the way the agency conducts these evaluations has serious weaknesses. Here are just a few of the key problems with the current process:

- It doesn’t allow for quick response to emerging science;

- It doesn’t assess risk based on real-world exposures; and

- It relies heavily on corporate safety data that is not peer-reviewed or available to the public.

An enforcement gap

Under our current registration and labeling system, any use guidelines or restrictions — what crops can be sprayed with the product, any limitations on volume, timing or location of use, whether the product can be used for indoor pest control — are simply spelled out on the labels.

It’s then up to state governments to enforce these requirements, which are sometimes quite complex. And, unfortunately, states rarely have adequate resources for the job. Even if enforcement were strong enough to stop violations, in case after case pesticides “applied as directed” have still been shown to cause harm.

For example, even when label instructions for drift-prone pesticides are followed precisely, the chemicals are often detected in air samples taken at nearby schools, homes and farms — at levels known to cause health harm and/or crop damage.

Less is more

The bottom line? Our current system does very little to encourage the safest form of pest control.

Pesticide rules must be strengthened right now to protect farmers, farmworkers, rural communities — and children everywhere. Critical, overdue improvements would direct regulators to:

- Take swift action when new, independent science sounds the alarm;

- Keep new products linked to cancer, neurodevelopmental or reproductive harms off the market;

- Strengthen standards for pesticide residues on food to protect the most vulnerable;

- Establish and enforce protective no-spray zones for drift-prone pesticides; and

- Put strong measures in place to reduce farmworkers’ on-the-job exposures.

These important protections are not, however, long term solutions.

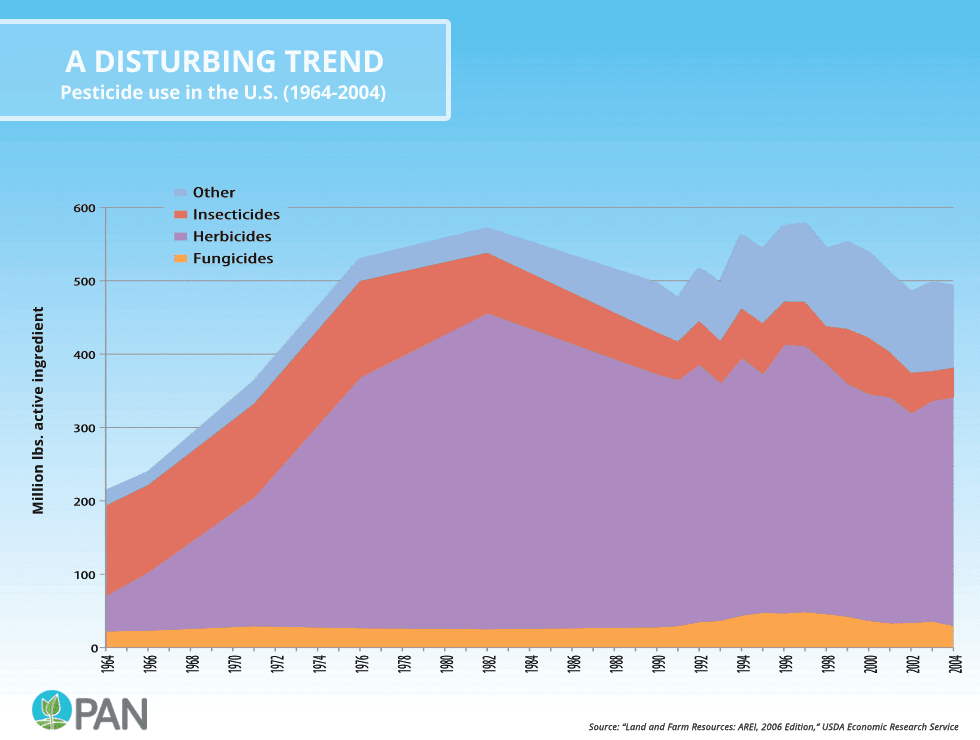

A billion pounds per year is just too much — and this doesn’t even include use on lawns, gardens, homes and buildings. It’s time for an aggressive national pesticide use-reduction goal, backed up with use reporting to monitor progress and policies that support safer pest control, including meaningful investments in agroecological farming.